When the Quarrels Disappear

Written and Translated by Nguyên Giác

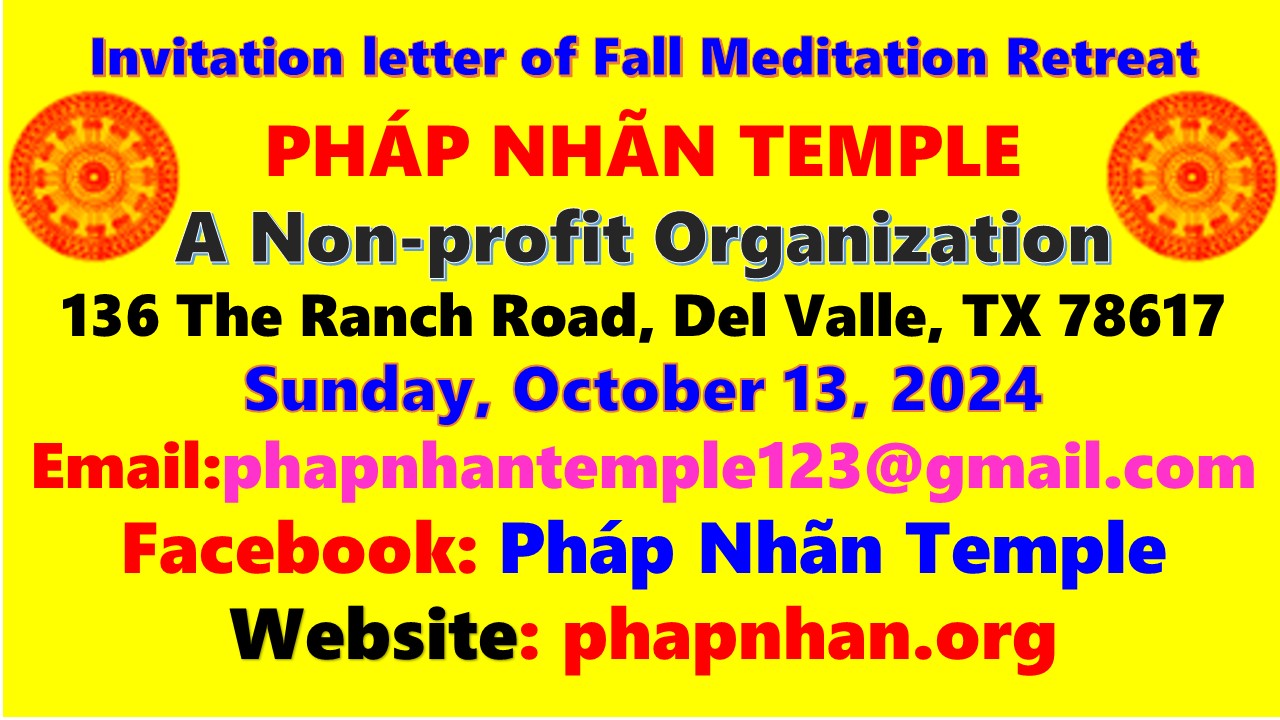

We often find ourselves caught in the midst of quarrels. It is rare to navigate this world without encountering quarrels. Here, we are not referring to political conflicts or those between religions; such quarrels have sparked bloody wars for thousands of years. Even at the gates of Vietnamese temples, we sometimes encounter quarrels—not only between sects but also within the hearts of individuals. In truth, for those who comprehend the Dharma, it becomes clear that there is no longer a need for quarrels.

In the mind of a practitioner, the most significant debate revolves around discovering the path to transcend the cycle of birth and death, specifically the journey from samsara to Nirvana. In other words, we must learn to navigate from the conditioned world to the unconditioned realm. When we assert that an unconditioned world exists, language can mislead us, as the unconditioned world, or Nirvana, is not situated in any of the four cardinal directions: East, West, South, or North.

The conditioned world is what manifests through our six senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch, and thought. All phenomena in the conditioned world are impermanent, unsatisfactory, and devoid of a permanent self. Within this realm, we observe the cycles of birth, aging, sickness, and death. However, Zen teaches that Nirvana exists within this very experience, for the wave does not separate from the water, and the reflection does not depart from the mirror.

Contrarily, despite their appearance as ordinary people walking, standing, lying, and sitting, the Buddha and the holy monks resided in Nirvana, the unconditioned realm. The Buddha and the holy monks of ancient times still preached the Dharma, begged for alms every day, spoke, ate, and drank, but they actually lived with the unborn.

In the MN 140 Sutta, the Buddha stated that a practitioner who is free from delusions is known as a tranquil recluse. At that moment, although he remains in this world, he is not subject to birth, aging, or death. During his lifetime, even though his hair may turn white, he is no longer considered old. While he may occasionally cough, experience flu symptoms, or suffer from back or leg pain, he is genuinely free from illness. He is truly no longer dead, even though he must eventually stop breathing and surrender his life for cremation upon passing.

Thus, when a practitioner attains liberation, their mind no longer oscillates between truth and delusion. The entirety of the six senses of the Buddha and the holy monks is entirely authentic. However, unlike changing clothes or identity cards, the liberated mind is not an external entity that replaces the deluded mind.

The Shurangama Sutra states that when a cultivator realizes the true mind, he observes the fundamental afflictions and ultimately ends all delusions. At that moment, while he sees, hears, and perceives, delusions will cease in his mind, revealing what is true and eternal. Similar to a play, every character on stage is merely a role. Those who see beyond the stage will clearly recognize the roles, and such individuals will no longer cry or laugh along with the actors.

Vietnamese Zen history tells of Zen Master Chân Nguyên (1647-1726), who restored the Trúc Lâm Zen sect. Chân Nguyên wrote a four-line poem explaining that for those who have realized the Dharma of the unconditioned in the mind—that is, the true nature of the mind—all six senses reveal the truth of permanence, stillness, and immutability.

The poem has been transformed into prose as follows: All phenomena are clearly revealed throughout the day. This is the nature of unobstructed awareness. It is the eternal truth, perceived through the six senses. All dharmas, whether vertical or horizontal, are distinctly recognized and understood.

Zen Master Trần Thái Tông (1218-1277) said that the constant nature of awareness does not come from outside and intrude into our body and mind. This constant awareness is intrinsically pure, complete, and untarnished by a single particle of dust. Trần Thái Tông wrote in the book Lục Thì Sám Hối Khoa Nghi that it is only because there is “Năng sở nương nhau, Phật ta hai ngả,” meaning because sentient beings grasp that there is an “I am” and a “mine” that they see two different sides, Buddha and me.

This Zen master likened delusion to the wind that stirs up waves on the surface of the mind’s water; in a similar vein, delusion can be compared to the dust that obscures the reflection in the mind’s mirror. Trần Thái Tông stated that to achieve purity in both body and mind, one must calm the wind so that the waves cease; likewise, when the dust is removed, the mirror becomes clear.

Trần Thái Tông said that people mistakenly perceive Buddha and sentient beings as two distinct paths, i.e., Nirvana and the realm of afflictions. In reality, there is no difference at all, as the wave represents water and the image represents the mirror.

Written and translated by Nguyên Giác

Vietnamese Zen history recounts the story of Zen Master Định Hương, who lived in the 11th century and belonged to the Vô Ngôn Thông lineage. As a child, Định Hương studied under Zen Master Đa Bảo at Kiến Sơ Pagoda. After 24 years of diligent study, Định Hương gained a profound understanding of the teachings of this Zen lineage. Zen Master Đa Bảo instructed Định Hương to communicate with others as if he were blind and deaf. This raises a question for us, people living ten centuries later: Why must we see as a blind person and hear as a deaf person?

Here, we can recall a poem by Maha-Kaccana in the Theragatha, numbered Thag 8.1. This poem consists of eight stanzas, translated from Pali by Bhikkhu Bodhi. The last two stanzas are presented below.

One hears all with the ear,

One sees all with the eye,

The wise man should not reject

Everything that is seen and heard.

One with eyes should be as if blind,

One with ears as if deaf,

One with wisdom as if mute,

One with strength as if feeble.

Then, when the goal has been attained,

One may lie upon one’s death bed.

The monk Maha-Kaccana was an Arhat and a distinguished disciple of the Buddha. The poem is straightforward, and its meaning is clear; however, the underlying significance is likely profound. Did the Zen lineage of Zen Master Đa Bảo originate from Maha-Kaccana’s lineage? It is possible, but history does not document this connection clearly.

In the late 20th century, a Vietnamese Zen nun wrote a poem that bore a striking resemblance to Maha-Kaccana’s poem. This nun was Venerable Thích Nữ Trí Hải (1938-2003). She titled her poem “Wooden Person” and recorded its three stanzas.

This is a miraculous corpse that not only eats and sleeps, but also occasionally walks, all while remaining devoid of thoughts.

This individual contemplates the wonders of beautiful landscapes, much like a wooden figure gazing at flowers. Her mind resembles a lake reflecting the moon, with rocks and mountains arranged before her eyes.

This person completes this extraordinary universe, especially when her mind remains still, resembling a walking corpse.

The 13th century saw references to the image of a wooden figure in Vietnamese Zen poetry. Zen Master Tuệ Trung Thượng Sỹ (1230 – 1291) wrote that a Zen practitioner should be like a wooden figure singing the song of the unborn and like a stone girl playing an ancient type of trumpet. Clearly, everyone understands that the wooden figure cannot open its mouth, and the stone girl cannot move.

In the poem mentioned above, Venerable Thích Nữ Trí Hải expressed that she lived like a corpse, yet she knew how to eat, sleep, walk, admire flowers, and recognize the stillness of the mind while it remained motionless. Clearly, this describes a person who is walking, standing, lying down, or sitting in meditation. It could represent the First Jhana, when the mind has relinquished desire and unwholesome states of mind. Alternatively, it may refer to the Second Jhana, where language becomes silent. This analysis aims to provide readers with a few insights to enhance their understanding of our ancestors’ practices, without attempting a complex evaluation.

We can recall the SN 35.240 Sutta, where the Buddha taught how to practice like a turtle. When the jackal came to disturb the turtle, the turtle withdrew its entire body, legs, and neck into its shell, leaving no opening. According to the Buddha, the Evil One lurks constantly, and if a practitioner exhibits carelessness in their eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind, the Evil One will guide them into the three realms and six paths.

At that time, the Buddha taught that practitioners must guard their senses. Specifically, when the eyes perceive an object, one should refrain from clinging to general characteristics or specific details; in doing so, greed, anger, and delusion will not arise. Similarly, this principle applies to the ears hearing sounds, the nose detecting scents, the tongue tasting flavors, the body experiencing sensations, and the mind engaging in contemplation.

However, Vietnamese Zen masters do not look at the problem in an antidotal way, like a turtle defending against a jackal. In the poem of Venerable Trí Hải, it is said that she lives exactly like a corpse, but her mind is revealed like the surface of a calm lake reflecting the bright moon,