Dharmacharya Andrew. J. Williams

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BUDDHISM Part 7 –

GRECO-BUDDHIST INTERACTION

◆● ════ ◆◇◆════ ●◆●

“At the beginning of the Silk Road, at the crossroads between India and China (modern day Afghanistan, northern Pakistan, and Tajikistan), Greek Kingdoms had been in place since the time of the conquests of Alexander The Great around 326 BCE and continued for over 300 years. Firstly, the Seleucids from around 323 BCE, then the Greco-Bactrian Kingdoms from around 250 BCE and finally the Indo-Greek Kingdom, lasting until 10 CE.

The Greco-Bactrian King Demestrius 1 invaded the Indian Subcontinent in 180 BCE, establishing an Indo-Greek Kingdom that was to last in parts of the Northwest of South Asia until the end of the 1st Century CE.

Buddhism flourished under the Indo-Greek and Greco-Bactrian kings, and it has been suggested that their invasion of India was intended to show their support for the Mauryan Empire and to protect Buddhism from the alleged religious persecutions of the Shunga’s (185-73 BCE).

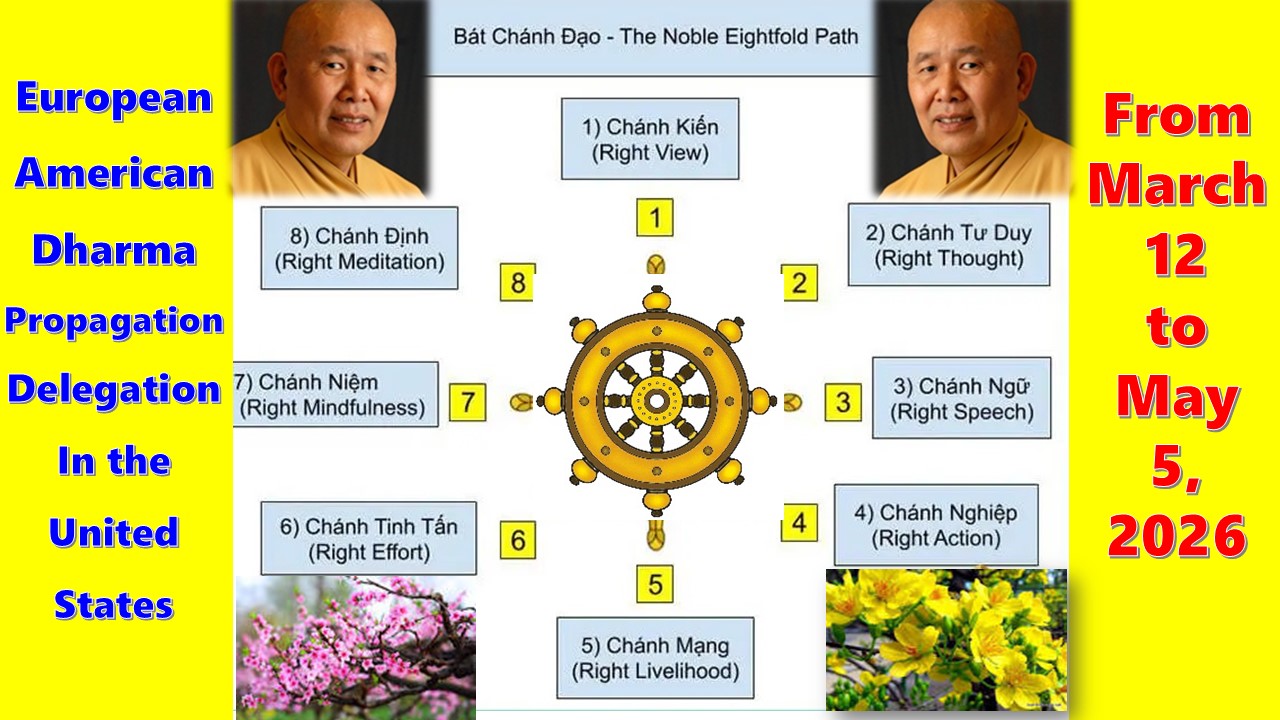

One of the most famous Indo-Greek kings was King Menander, who reigned from 160 BCE to 135 BCE. He converted to Buddhism and is presented in the Mahayana tradition as one of the great benefactors of the Dharma, on a par with King Asoka or the later Kushan King Kaniska. Menander’s coins bear the mention of the ‘Saviour King’ in Greek, with some bearing designs of the Eight-Spoked Dharma Wheel.

Direct cultural exchange is also suggested by the dialogue in the ‘Milindapanha’ (Recorded Questions of King Milinda), around 160 BCE, between King Menander and the Buddhist monk Nagasena, who was himself a student of the Greek Buddhist monk Mahadharmaraksita.

Upon Menander’s death, the honour of sharing his remains was claimed by the cities under his rule, and they were enshrined in stupas, in a parallel with the historic Buddha. Several of King Menander’s Indo-Greek successors inscribed “Follower of the Dharma”, in the Kharosthi script, on their coins, and depicted themselves or their divinities forming the Vitarka Mudra (Sacred Buddhist Hand-Gesture).

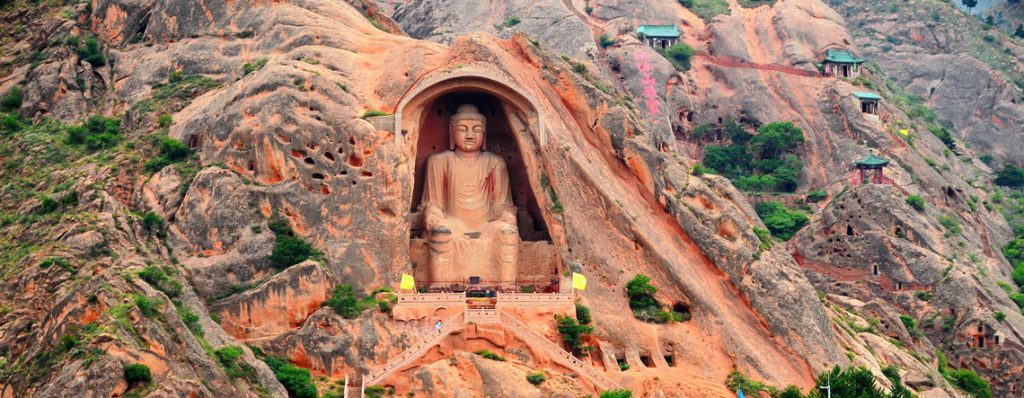

It is also around the time of initial Greek and Buddhist interaction that the first anthropomorphic (human-like) representations of the Buddha are found, often in realistic Greco-Buddhist style. The former reluctance towards anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha, and the sophisticated development of aniconic symbols to avoid it, seem to be connected to one of the Buddha’s teachings, reported in the Digha Nikaya, that discouraged representations of himself after the extinction of his body. Probably not feeling bound by these restrictions, the Greeks were the first to attempt a sculptural representation of the Buddha.

In many parts of the Ancient World, the Greeks developed syncretic divinities, that could become a common religious focus for populations with different traditions. A well-known example is the syncretic God Sarapis, introduced by Ptolemy 1 in Egypt, which combined aspects of Greek and Egyptian Gods. In India as well, it was only natural for the Greeks to create a single common divinity by combining the image of a Greek God-King (The Sun-God Apollo, or possibly the deified founder of the Indo-Greek Kingdom, Demetrius), with the traditional attributes of the Buddha.

Many of the stylistic elements in the representations of the Buddha point to Greek influence. For instance, the Greco-Roman toga-like wavy robe covering both shoulders (more exactly, its lighter version, the Greek himation), the contrapposto stance of the upright figures such as the 1st-2nd Century Gandhara standing Buddha’s, the stylised Mediterranean curly hair and topknot (ushnisha), apparently derived from the style of the Belvedere Apollo (330 BCE), and the measured quality of the faces, all rendered with strong artistic realism. A large quantity of sculptures combining Buddhist and purely Hellenistic styles and iconography were excavated at the Gandharan site of Hadda.

Several influential Greek Buddhist monks are recorded. Venerable Mahadharmaraksita (literally: Great Teacher/Preserver of the Dharma) was a Greek Buddhist head monk, according to the ‘Mahavamsa’ (‘Great Story’ – Pali chronicle of Sinhalese history), who led Thirty Thousand Buddhist monks from the Greek city of Alasandra (Alexandria of the Caucasus, around 150 km north of today’s Kabul in Afghanistan), to Sri Lanka for the dedication of the Great Stupa in Anuradhapura during the rule of King Menander 1 (165 BCE-135 BCE). Mahadharmaraksita was one of the missionaries sent by the Mauryan emperor King Asoka to propagate the Buddhist teachings and way of life.”

●◆● ════ ◆◇◆════ ●◆●

~Dharmacharya Andrew. J. Williams~

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BUDDHISM Part 8 –

THE CENTRAL ASIAN EXPANSION

●◆● ════ ◆◇◆════ ●◆●

“A Buddhist gold coin from India was found in northern Afghanistan at the archaeological site of Tillia Tepe, and dated to the 1st Century CE. On the reverse, it depicts a lion in the moving position with a Nandipada (literally: foot of Nandi) (an ancient Indian symbol) in front of it, with the legend in Kharoṣṭhi script reading “Sih(o) vigatabhay(o)” (“The lion who dispelled fear”).

The Mahayana Buddhists symbolised Buddha with animals such as a lion, an elephant, a horse or a bull. A pair of feet was also used. The symbol called by the archaeologists and historians as “Nandipada” is actually a composite symbol. The symbol at the top symbolises the Middle Path, the Buddha Dharma. The circle with a centre symbolises a chakra (wheel). Thus, the composite symbol symbolises a Dharma Chakra (Dharma Wheel). Thus, the symbols on the reverse of the coin jointly symbolise the Buddha turning the Wheel of Dharma.

In the ‘Lion Capital’ of Saranath, India, the Buddha turning the Wheel of Dharma is depicted on the wall of a cylinder with a lion, an elephant, a horse and a bull turning the Dharma Wheel. On the obverse, an almost naked man only wearing a Hellenistic chlamys (cloak) and wearing a head-dress turns a Dharma Wheel. The legend in the Kharoṣṭhi script reads “Dharmacakrapravata(ko)” (“The one who turned the Wheel of the Law”).

It has been suggested that this may be an early representation of the Buddha. The head dress symbolises the Middle Path. Thus, the man with the head dress is a person who adheres to the Middle Path. Thus, on both sides of the coin, we find the Buddha turning the Wheel of Dharma.

We should note that as no scientific study on the literary and physical symbolisation of the Buddha and Buddhism was conducted by these particular archaeologists and historians, possibly due to a lack foresight and the many restrictions they may have been faced with at the time, so unfortunately only loose interpretations were given on the coins, seals, inscriptions and other archaeological finds.”

●◆● ════ ◆◇◆════ ●◆●

~Dharmacharya Andrew. J. Williams~