THE STRANGE WORKINGS OF KARMA:

THE INFLUENCE OF THÍCH GIÁC ĐỨC ON MY LIFE

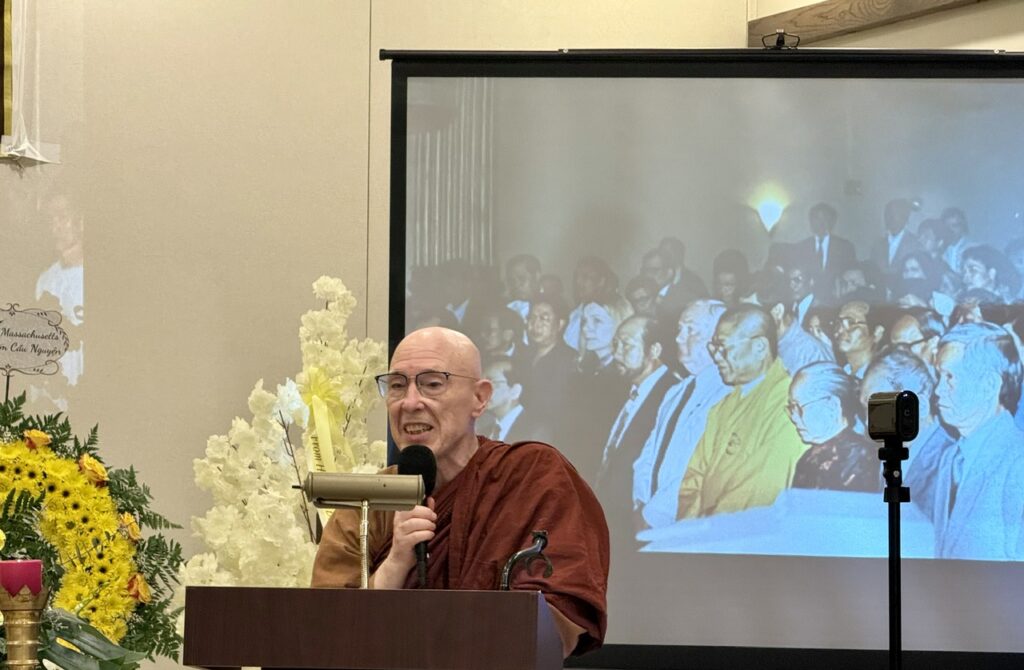

Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi

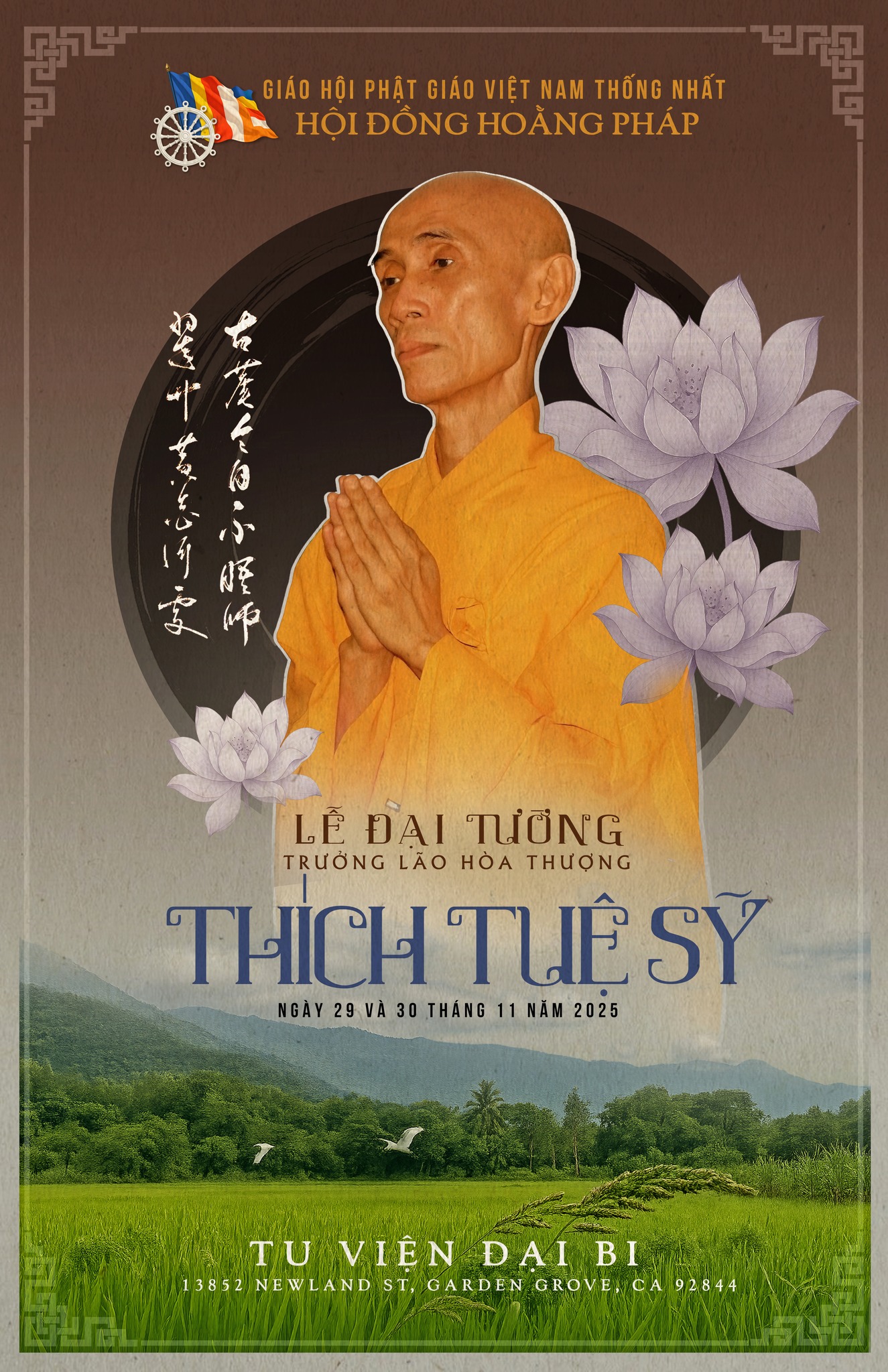

Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi spoke on November 9 at the funeral service of the late Senior Dharma Master, Most Venerable Thích Giác Đức at a Boston Funeral Home, MA.

Sometimes the chance meeting with a single person can change the entire course of our life in ways we never could have foreseen. For example, you might have planned to study business management in college, but you take a course in literature from a wonderful professor who inspires you with his lectures on Shakespeare and modern poetry. You decide to major in literature instead of business management, and you wind up becoming an English teacher rather than a businessman.

In my own case, the person who changed the course of my life was Ven. Thich Giac Duc. How did this happen? I entered Claremont Graduate University in September 1966 to pursue a PhD program in philosophy. I was already interested in Buddhism, which I had begun to read about while I was in college. I had even tried to meditate on my own, but soon gave up, unsure how to sustain my practice without competent guidance.

At the beginning of my second semester at Claremont, in February 1967, one day I saw a brown-robed man walking through the graduate residence hall. I identified him as a Buddhist monk, and someone told me he was from Vietnam. I didn’t have a chance to speak to him, but a few days later, a group of my fellow graduate students invited me to a social gathering they were holding in a lodge on Mount Baldy—a large mountain near Claremont—and when I arrived, I saw that the Vietnamese Monk was also there.

Although I had not spoken to him before, he came up to me and told me he felt we had a lot in common, that we had some kind of connection. He even said he thought I had the ability to understand Buddhism. This struck me as strange, even puzzling, since he had no way of knowing that I was already interested in the Dharma. There were about twenty other students present, but he somehow chose me out of the crowd as a person with whom he felt a connection. I told him that I was indeed interested in Buddhism, and in particular that I wanted to learn how to meditate. He told me he could teach me and we made an appointment for me to visit him the following week.

Thus, one day that week, I came to his room in the graduate residence hall, and he gave me my first instructions in meditation, on mindfulness of breathing. I started to practice, first 30 minutes in the morning and evening, and later I increased this to 40 minutes and then 50 minutes twice a day. I visited him from time to time to report on my practice, and on these occasions, he would also teach me more about Buddhism. As I experienced the benefits of meditation, my conviction in the value of the Dharma increased.

One day, about two months after I started to meditate, the thought suddenly came into my mind: “I want to become a monk.” And so, when I next visited him, I asked whether he could ordain me, and he told me that he would write to the Sangha authorities in Vietnam to ask for their permission.

When I look back on this now, it seems my thought of being ordained as a monk was a crazy thought, inexplicable on rational grounds. I was only 22 years old, I had only been practicing meditation for two months, and I had no idea what being a Buddhist monk would involve. But I think Ven. Giac Duc had some insight into my character and may have seen that we had been karmically connected in a past life. He wrote to the Sangha elders in Vietnam and received permission to ordain me as a novice in the Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Sangha.

The ordination took place on May 23, 1967, the Vesak full moon day that year. Thay had a friend in Los Angeles, another Vietnamese monk named Ven. Thich Thien An, who had been a visiting professor at UCLA. Ven. Thien An arranged for us to conduct the ceremony in a Japanese Buddhist temple in Los Angeles, and there I became a novice monk. Thay gave me the Vietnamese name, Giac Tue, which in Pali or Sanskrit became “Bodhi.”

In the fall of 1967, Thay and I moved to a small house in the town of Claremont. A mutual friend, Conn Hickey, and another graduate student named Tatsuo Muneto—a Japanese Buddhist priest from Hawaii—joined us for meals. Over the next few years, the four of us had dinner together every evening, taking turns doing the cooking—a task at which Thay excelled. I continued to live with Thay for the three years he was at Claremont, until he completed his PhD and left to return to Vietnam in the spring of 1970.

Through Thay, I learned not only the theory and practice of Buddhism but about the struggles of the Vietnamese Buddhists. I learned how Buddhism in Vietnam had been ruthlessly suppressed by the government of Ngo Dinh Diem; how Thay himself had been imprisoned and beaten and tortured in prison; how Buddhist monks and nuns, to defend the Dharma, had set themselves on fire. And I learned how the Buddhists found themselves squeezed between the communists on one side and repressive governments on the other, regimes supported by successive U.S. administrations. Thay presented to me the vision of an actively engaged Buddhism devoted not only to personal awakening but to social transformation grounded in the Buddhist values of compassion and human equality.

During the time we lived together, Thay would discuss with me his plans for my future as a Buddhist monk. At the time, since there were no training monasteries in the U.S., it wasn’t possible to receive monastic training in this country. So we determined that I would go to Asia to train and take full ordination. Thay realized that, because of the war, it wouldn’t be possible for me to study in Vietnam. He originally thought I should go to India, to study at the Nalanda Buddhist Institute. Later, however, he thought I would be better off in a traditional Buddhist country and suggested I should go to Sri Lanka. This meant that I would switch lineages, from Vietnamese Mahayana to Sri Lankan Theravada, but Thay had immense respect for the Theravada tradition and for the Pali Canon. Already in Claremont we had ordered the entire Pali Text Society’s English translations of the Nikayas, and we often referred to these texts and to their counterparts in the Chinese Agamas.

After Thay returned to Vietnam, I met several Sri Lankan monks who were passing through Los Angeles, and one of them—Ven. Piyadassi Thera of Vajirarama in Colombo—connected me to a senior Sri Lankan monk, Ven. Ananda Maitreya, the head (mahanayaka thera) of the Amarapura branch of the Sri Lankan Sangha, who was to become my ordination teacher. When I finished my doctoral dissertation at Claremont, I left the U.S. with Sri Lanka as my destination, but on route I stopped in Vietnam for two months, where I stayed mostly at the Giac Minh Pagoda, Thay’s temple in Saigon. At the time, Conn Hickey was living in Saigon, doing research on Vietnamese Buddhism.

I left Vietnam in October 1972, and after arriving in Sri Lanka I re-ordained into the Theravada order, first as a novice and six months later as a bhikkhu. After three years in Sri Lanka, I had thought of returning to Vietnam to visit Thay again. In March 1975, I traveled to India, where I planned to spend the rains retreat, go on pilgrimage to the Buddhist holy places, and then visit Vietnam toward the end of the year. However, in April 1975, Vietnam fell to the communists and Thay fled to the U.S. And so, when my time in India came to an end, I returned to Sri Lanka for the next two years. I came back to the U.S. in 1977 and then returned to Sri Lanka in 1982, where I remained for the next twenty years, until I came back to America in 2002.

Through all these years, I have always been grateful to Thay as the person who set me on the path of a Buddhist monk. If I had not met Thay, my destiny would have been quite different. I might have become a professor of philosophy at a college or gone into some other field. However, it has been my great fortune that I have walked the path of a Buddhist monk for 58 years now, and it was my encounter with Ven. Thich Giac Duc that set me in this direction.

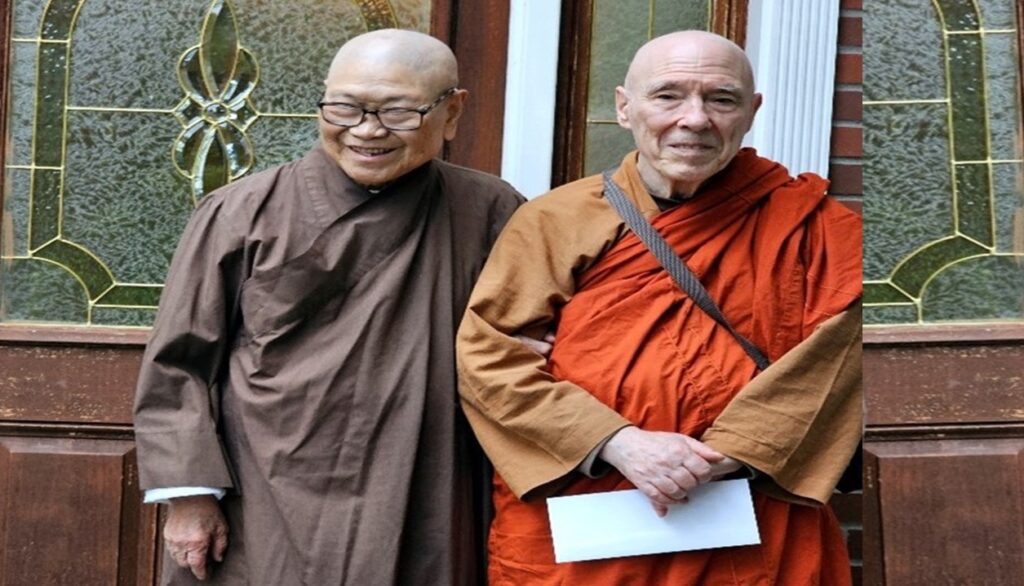

I visited Thay at his home in Newton in 2015 and 2017, but had not seen him since then. Earlier this year, I spent three weeks in Vietnam, the first time I had been in the country since 1972. I even briefly visited the Giac Minh Pagoda, but, since the resident monks were away, I could view it only from the outside. This visit brought back strong memories of my past association with Thay. When the Bangladeshi Buddhists invited me to be the guest speaker at their annual gathering in Cambridge on August 31, I accepted the invitation with the idea that it would give me the chance to meet Thay again. On August 30, I visited Thay and Dung at their home in Newton. It was a very joyful meeting. I found Thay, who had just turned 90 in mid-August, in reasonably good health and bright spirits, and we were both delighted to see each other again. Thay even told me my visit brought tears to his eyes. I regretted that I hadn’t come up to Newton more often and thought we would have the chance to meet many more times.

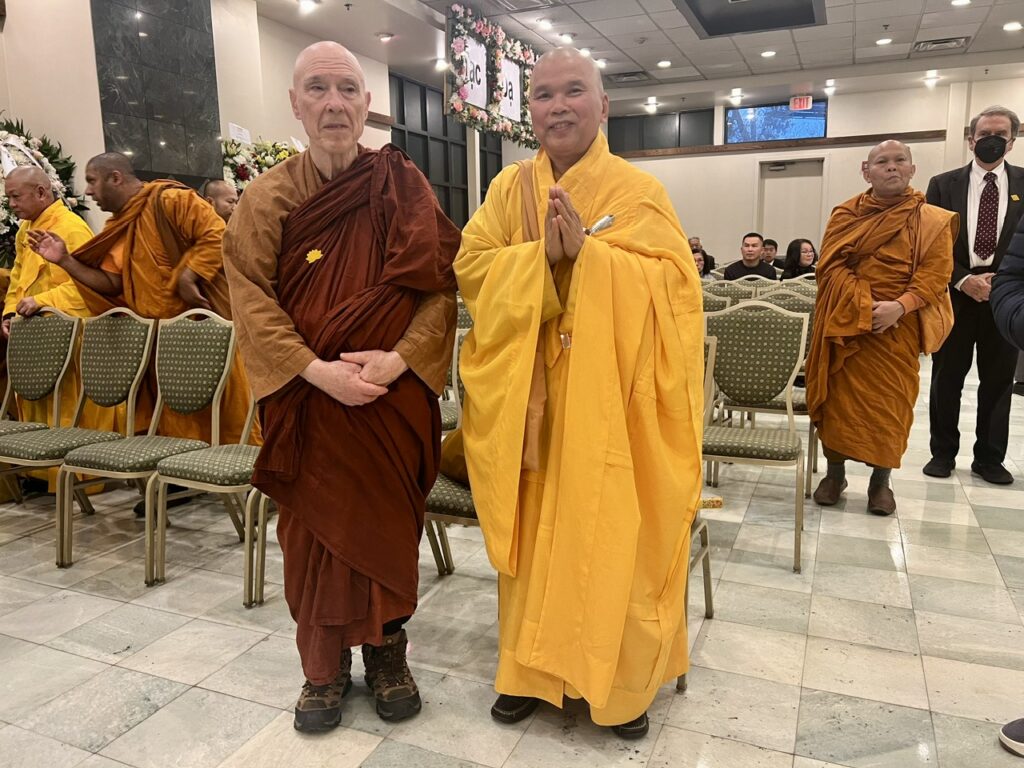

With Thích Giác Đức on Aug. 30, 2025

This, however, was not to be. In mid-October, Conn informed me that Thay had a heart attack and was hospitalized in Boston. As soon as I could finish some matters at Chuang Yen Monastery, where I now live, I came to Boston to see Thay, and it was a great blessing that I could be with him during his last week in this world. Conn had also flown from California to Boston to be with Thay. Even though he could not open his eyes or speak, I think he understood me when I told him how grateful I was for our friendship and for his influence on my life.

It seemed to me that this last week we spent together in the intensive care unit—along with Conn—completed the circle that began 58 years earlier in Claremont. Between 1967 and 1970, the three of us spent time together each evening, discussing Buddhism, the Vietnam war, and other vital issues. Now we spent the week together again in his room at the hospital, but this time joined by loving silence rather than conversation.

I certainly don’t think that Thay’s passing marks the end of our relationship. Thay lives on in my mind and heart. He inspired in me the idea that the purpose of following the Buddhist path is not only to seek one’s own liberation but to work to create a better world—a world of peace, justice, and dignity for everyone. He always emphasized the need to put others before oneself, and he himself exemplified this in practice, embodying the spirit of the bodhisattva. His example continues to inspire my life as a monk, especially at the present time, when people around the world are facing so much pain, even here in the United States.

Although I don’t have any memories of past lives, I strongly feel that Thay and I encountered each other through a close karmic connection going back over previous lives. I also believe that in time, as the wheel of samsara turns, we will meet again to walk the Buddha’s path together, hand in hand.

Dear Ven. Thích Trừng Sỹ,

Thank you for your heartfelt email message. I was happy to meet you at the funeral ceremony of Ven. Thích Giác Đức, my first Buddhist teacher.

I attach here the English text of my eulogy at the ceremony. I made some revisions and additions to the original article and included a photo of Ven. Giac Duc and myself when we met at his home in Newton on August 30th this year.

You can post the article on your website and perhaps send it to any Vietnamese Buddhist magazine.

With all best wishes,

Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi

Venerable Thích Trừng Sỹ had the good opportunity to take a photo with Bhikkhu Bodhi on November 9, 2025, during the funeral service of the late Senior Dharma Master, Most Venerable Thích Giác Đức.