Myanmar’s IBEC to join Europe’s largest Buddhist Park project in Spain

IBEC Sayadaw and responsible personnel of the Lumbini Garden project meet.

The International Buddhist Education Centre (IBEC) has announced its participation in the Lumbini Garden project in Spain, which is set to become the largest Buddhist Park in Europe.

This significant initiative will involve contributions from several countries, including Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Sri Lanka, China, Hong Kong, Nepal, Bhutan, and Chinese Taipei. The project will feature advanced Buddhist education programmes supported by IBSC (Thailand), SSBU, SIBA, and IBEC-Myanmar.

IBEC Sayadaw, serving as a project board member, will oversee the construction of the Myanmar Temple Embassy and a replica of the Shwedagon Pagoda.

Initially, the project faced challenges as the original site was deemed unsuitable due to Spanish environmental regulations. However, a new location has been secured, and the Spanish government has issued the necessary construction licence. A redesigned plan will be developed, and the project will move forward at the new site.

On 30 November, IBEC Sayadaw held discussions with project officials in Cáceres, Spain, to finalize plans and ensure the smooth implementation of the project. — ASH/TMT

https://www.gnlm.com.mm/myanmars-ibec-to-join-europes-largest-buddhist-park-project-in-spain/

A small Spanish city’s bid to build Europe’s biggest Buddha

(RNS) — The 6,000-ton white jade Buddha statue will overlook a sprawling group of temples and monasteries just kilometers from the city center. But suspicions of the project abound.

The old town of Cáceres, Extremadura, Spain, in 2019. (Photo by Alonso de Mendoza/Wikipedia/Creative Commons)

The old town of Cáceres, Extremadura, Spain, in 2019. (Photo by Alonso de Mendoza/Wikipedia/Creative Commons)

(RNS) — Every November, the Spanish town of Cáceres holds the Medieval Market of the Three Cultures to commemorate its history of religious coexistence, Spanish Inquisition aside. Before the Christian kingdoms united, kicked out medieval Spain’s Muslim rulers and expelled all the Jews in 1492, the Abrahamic religions are said to have lived in tolerant harmony. But the market’s name might need an upgrade soon. It will be difficult to ignore the 47-meter Buddhist statue the town plans to erect in a few years.

The project, started up by the Lumbini Garden Foundation, a Spanish association created in collaboration with the Nepalese city of Lumbini, envisions an up to 6,000-ton white jade Buddha statue overlooking a sprawling group of temples and monasteries just kilometers from the Cáceres city center.

Cáceres, with a population of 95,976 as of 2022, wants to become Buddhism’s headquarters in Europe. The project directors describe building a bridge between West and East, facilitating a greater understanding of spirituality and Asian-centric values within Europe at a time when people are increasingly turning their backs to religion, as well as to the reality that Asia is speeding ahead.

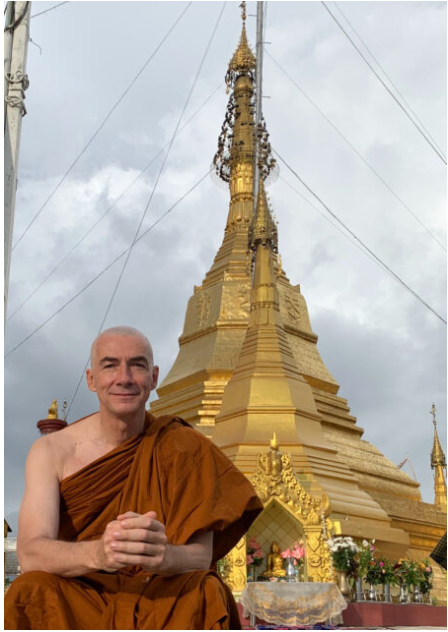

Ricardo Guerrero in Myanmar, in the summer of 2019, where he received temporary ordination as a Buddhist monk. (Submitted photo)

Ricardo Guerrero in Myanmar, in the summer of 2019, where he received temporary ordination as a Buddhist monk. (Submitted photo)

“The West, whether Americans or Europeans, know almost nothing of Asia. We live in a globalized world in which, little by little, the economic and demographic weight is pivoting towards Asia, and we cannot continue the luxury of developing without their knowledge,” Ricardo Guerrero, one of the patrons of Lumbini Garden Foundation, says.

Having turned away from Catholicism as a teenager, Guerrero found the spiritual answers he was searching for in Buddhism, which did not demand faith but rather provided a landline from a rational perspective, he said. He set up the Hispanic Association of Buddhism in Spain in 2012 and became a Theravada monk in Myanmar in 2019.

“I don’t have faith,” Guerrero says, a sentiment shared by an increasing swath of Spain. Just 36% of the population identifies as Catholic, with only 18% practicing, according to the Center of Sociological Research, a public body. This shift makes it even more pertinent and necessary to promote the messages of Buddhism, Guerrero believes.

“There is a way of understanding life, a series of values that we have in many ways lost here,” he said.

José Manuel Vilanova, president of the Lumbini Garden Foundation, told Religion News Service that young people, in particular, are interested in Buddhism as a philosophy.

“A philosophy that is not guided by a God, which is more in tune with a more natural attitude, in line with the laws of the universe,” said Vilanova.

Buddhism, he said, still emphasizes the importance of values such as empathy, compassion and kindness, but “without having to see it from a religious perspective, but rather from a humanistic perspective.”

That’s very attractive for young people, especially when many are “looking at pseudo-religions and other lifestyles for the answers that they don’t get from traditional religion,” Vilanova adds.

An artistic rendering of the proposed Lumbini Garden Foundation development in Cáceres, Extremadura, Spain, in 2019. (Image © Engineers’ & Surveyors’ Associates)

The Buddha project’s aims are lofty, especially for a small city, and there are those who question whether such grandiosity might doom it in the way of the biblical Tower of Babel.

Antonio Cancho Sierra of Guías-Historiadores de Extremadura, a tour guide and historian of the region, says everyone he knows is “at least suspicious” about a project that several other cities, with more relevance at the national level, including Madrid and Barcelona, have flatly rejected.

The financing appears opaque. Nobody knows exactly where the enormous amount of money required for the project will come from, says Cancho, and he is circumspect about the fact that it is provided by a foundation from Nepal, “a country much poorer than Spain.”

“At the moment, the only thing that has been done has been to bring a statue of Buddha that has ended up forgotten in a corner of a public building,” he says.

Critics point fingers at a culture and tourism subsidy of 281,229 euros, provided to the foundation in 2021, which has allegedly helped to pay for plane tickets to Nepal and for plane tickets to Nepal and other Buddhist-practicing countries for the project’s promoters.

Guerrero estimates there have been around 15 trips abroad but insists the foundation received the money through proper channels because it is doing something for the city’s immense benefit — and that many of those trips were paid for out of pocket by the foundation’s members.

“We have opened Extremadura’s doors to Asia,” Guerrero adds, referring to the Spanish region where Cáceres is located. Taking advantage of what he terms their missions to Asia, the foundation has promoted the province, its businesses and even its football teams — in December 2022, the local team, Club Polideportivo Cacereño, played two games against the Nepalese national team in Pokhara and Kathmandu in a campaign labeled “football for peace,” done in collaboration with the Lumbini Garden Foundation.

If the council paid an agency to do this sort of international advertising, the cost would have been “multiplied by 10, at least,” Guerrero insists, emphasizing that the money has also gone to a slew of cultural and educational activities.

“In the end, that money was spent in our own province,” says Tomás Vega, the key architect on the project.

Vega sympathizes with those who think that building a 47-meter statue of Buddha in their backyard might be a bit far-fetched. The mere cost of the material — a proposed 4,800 to 6,000 tons of white jade — is a “barbarity,” Vega admits.

But Cáceres will not have to foot the bill for its construction.

Apart from the subsidy, the project relies completely on substantial foreign donations from Asian countries, according to Guerrero, including the donation of the Buddha’s building blocks from Myanmar, a country that produces much of the world’s jade supply. Specifically, the Myanmar Gems and Jewelry Entrepreneurs Association “will be the donor,” according to a September 2023 dossier, “The Great Buddha Project,” written by the foundation.

“In Europe and America there is nothing similar. It’s hard to understand what it means. It’s going to be an icon,” Vega said.

Cáceres, red marker, in western Spain. (Image courtesy of Google Maps)

Cáceres, red marker, in western Spain. (Image courtesy of Google Maps)

Cáceres is a small city, and now it is “en la boca,” or in the mouths, of many Asian countries. Vega knows this firsthand, as the foundation has allowed him and others to make friendly inroads with Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn of Thailand, the king of Bhutan and important monks “on the pope’s level,” he said.

Money and rumors aside, the project still faces several obstacles. Environmental concerns about using protected public land nearly killed it a few months ago.

The original parcel of land that was picked, and provisionally signed off on, was the Arropé mount that is part of a special zone for protected bird species, or ZEPA. To build the Buddha, a portion of the ZEPA would have to be eliminated. Although the local council ultimately greenlit the project, the debate over the environmental value of the land continued and, ultimately, stakeholders on both sides decided to find a noncontroversial home for the project.

“We believed that the project could fall apart,” Vega admits.

But the new year promises a fresh start, with a final home for the Buddha approved by the city council in late December, in Cerro de los Romanos, about 10 kilometers from the original plot.

Even Antonio Diaz, president of Adenex, an environmental organization in Cáceres, who fought against the Buddha’s original placement, believes the plan for the new location is “positive” for Cáceres.

“Personally, I believe that a project like this is positive for a city like Cáceres — small and with not a lot of resources — both because of its possible economic repercussions and especially because of what it could mean for the promotion of tolerance and contact between cultures,” Diaz told RNS.

“But we must try to prevent this project from having repercussions on the natural environment or from conflicting with European directives and urban planning regulations,” he stressed.

Cáceres is a UNESCO World Heritage City, and Guerrero, Vega and Vilanova all refer to the potent “storytelling” element of bringing the Buddha to this part of Spain, where houses still have Islamic horseshoe arches and keen eyes can spot the hollow stone where Jewish mezuzas used to be attached. All made ample reference to building cultural bridges and continuing the city’s legacy as a bastion of religious conviviality.

But as Cancho noted, the truth is not always so picturesque. A large part of this tri-religious harmony is just a good story. “The myth of the three cultures is sustained from the political sphere for ideological reasons and, specifically in Cáceres, for tourist reasons, such as promoting that market,” Cancho says, referring to the November medieval market.

But before the tourists can start arriving, the ground still needs breaking.

This article was produced as part of the RNS/Interfaith America Religion Journalism Fellowship.